Millie Brigaud, Sofia Brooke, and Ambrose Pym

May 2024

One of Newport’s most famous music venues had been closed for more than a decade when it caught fire in the summer of 2018. It had hosted bands like the Sex Pistols, the Pretenders, and Siouxsie & The Banshees between the 70s and early 2000s.

The club, originally a Baptist church, was a cultural landmark and a listed building. It had gone by a series of names, including The Stowaway and Zanzibar, in its heyday. But after the venue closed for good in 2007, it fell into disrepair.

The church next door, also a listed building, bore the burden of its neighbour’s neglect. Rats from the abandoned site would journey into the church basement. And in the weeks – and days – leading up to the fire, local people expressed concern that the former club would collapse or burn.

Officials from the council and fire department had visited the old club just hours before it burst into flames.

“It was like a tinderbox really. As soon as it got going, all they could do was control it. They couldn’t stop it”, said Andrew Cleverly, the church pastor.

He watched the two buildings collapse in the fire, alongside local residents and the church youth group that was meeting in the building when the fire broke out. Stones and glass were “falling like confetti”, he said, and firefighters were worried the flames would travel through the pipes to other buildings.

A fire gutted the listed Bethel Community Church and neighbouring listed and derelict Zanzibar nightclub in Newport, Wales. June 2018. Andrew Cleverly.

These are just two of the many buildings listed for historical or architectural significance that have caught fire after having been left to rot. Many were lost years before, neglected by absentee owners, property developers, and local councils.

Public bodies in each UK nation grant listed status to sites they deem worthy of being “valued, celebrated and shared by everyone” and which Historic England say should be “passed on to future generations”.

But they are not being protected. When initial plans to convert historic buildings fall through, they’re neglected, subjected to vandalism and fires, then demolished.

The fire service in Grimsby, Lincolnshire has visited one former art college more than 60 times in the last decade, and there have been 17 fires at the derelict Margaret Beavan school in Liverpool in the last five years.

“It's about living history. The buildings tell a story about the place, our past, and where we are going in the future”, said Nick Small, a councillor who led Liverpool City Council’s successful lawsuit against developers that neglected a former convent. “We've got some really, really interesting buildings that have been in disuse for so long that people simply drive or walk past it and they don't necessarily know about the heritage”.

Neglected listed buildings provoke safety concerns and distrust in local councils. They also aggravate the UK’s affordable housing crisis in cities and stifle economic growth.

We wanted to know how many fires there had been in listed buildings since 2018. The public bodies that issue listed status didn’t know. Historic England – one of these bodies – does hold some data, collected on an ad-hoc basis from fire departments, social media posts, and news articles.

We also asked every fire department in the UK, through Freedom of Information requests, how many fires in listed buildings had happened in their areas since 2018.

Fire departments in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales couldn’t tell us. Some departments in England had records of them. Most didn’t record it at all.

We compiled a database by searching newspaper archives to record every instance we found of a fire in a listed building, noting if the buildings were derelict or abandoned. This only gave us a partial image, but it is still the best publicly available database.

Comparing Freedom of Information requests, our own data, and Historic England records, it is evident no public body in the UK understands how many listed buildings are catching fire.

The complete database is available here.

If you have anything you think should be added to our database and map, please send us an email at listedfires@gmail.com.

There are more than 370,000 listed buildings in England alone. But the Home Office, which is in charge of fire services, does not ask services to record whether a building fire they attend is in a listed building.

“I've been in the fire service for quite some time, and I don't think there's been that many fires in listed buildings that statistical data would make a difference on. But it could be worth looking at”, said Jamie Windsor, a fire investigator for South Wales Fire & Rescue Service. It would take minimal effort to include a box to check on a building’s listed status, he said.

Windsor and his colleagues agreed that it’s “quite possible” they’ve extinguished fires in buildings without knowing they were listed.

Cadw, the Welsh body that looks after historic buildings, say that while there aren’t figures on how many listed buildings have caught fire, they monitor all of them every five years to establish “the risk to a building from heritage crime, including arson or accidental fire”. Cadw have also launched a grant scheme to help local authorities protect listed buildings.

Charlie Harris, National Fire Advisor at Historic England, worked as a firefighter for 42 years. He and others at Historic England have asked the Home Office to collect data on fires in listed buildings with no success, he said.

“It’s not up to me to speculate why they don’t want to collect the data or why they see no reason to”, Harris said, but he noted that the Home Office does collect and publish data on the number of animals rescued and obese patients moved.

The Home Office declined our request for comment.

Search the map below for fires in derelict listed buildings since 2018. Each event is accompanied by a timeline of events surrounding the fire. This is a living project – please email us at listedfires@gmail.com with cases we should add to the map.

“We’ve lost so much in Northern Ireland in the last 30 or 40 years just due to neglect and arson”, said Sebastian Graham, Heritage at Risk Officer for Ulster Architectural Heritage.

But derelict buildings only seem to garner attention when they’re on fire, and after some days of uproar, they’re forgotten, Graham said.

Herdman’s Mill in Tyrone attracted national attention when it first went up in flames, but this has fallen away.

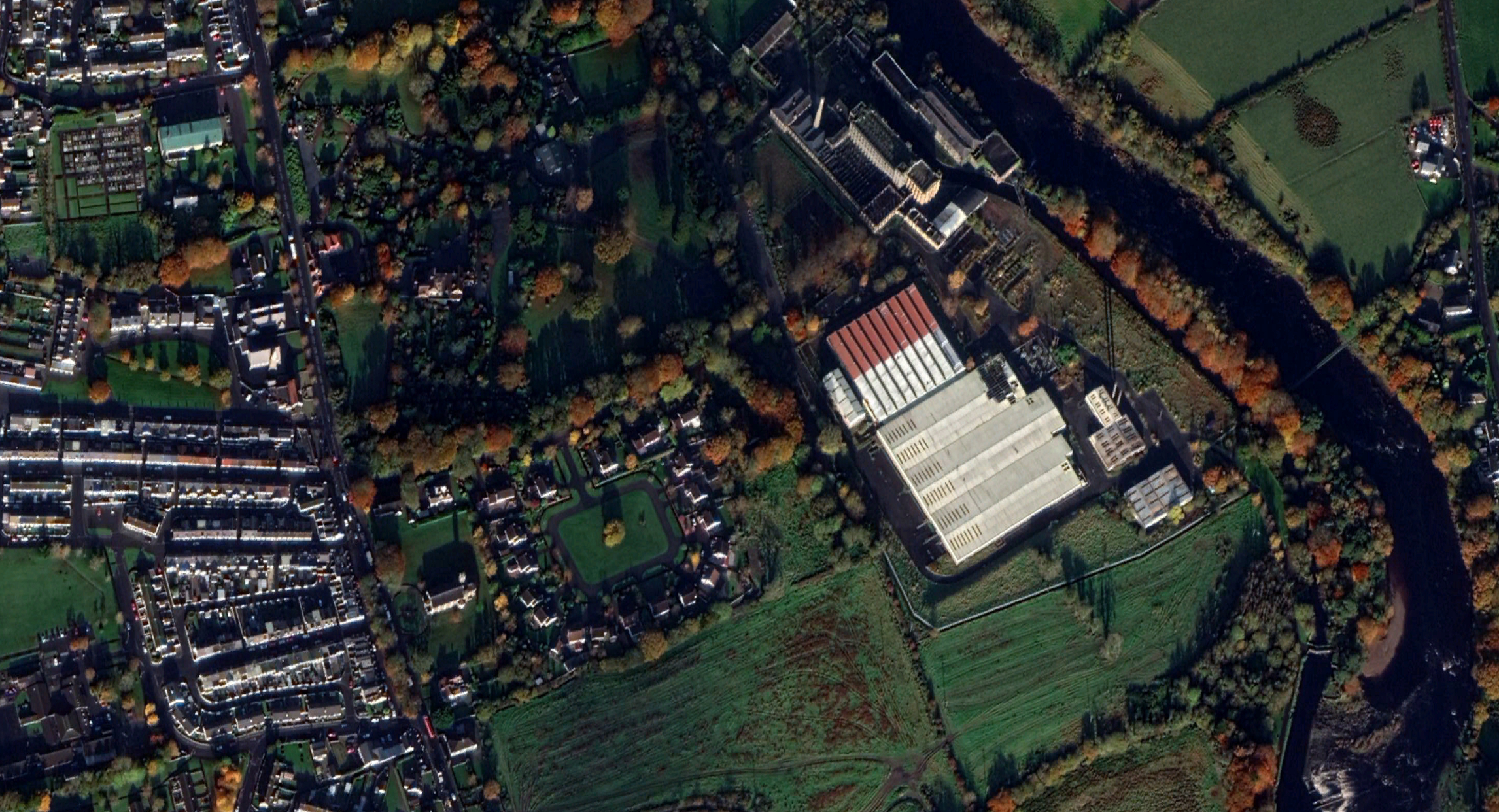

In 2004, the 172-year-old linen mill ceased spinning. Herdmans Limited had plans to restore its listed yellow brick buildings and towering chimney, but it couldn’t secure the money required and the company went into administration in June 2011.

A month later, the listed buildings were badly damaged in a fire. Though the event prompted the Northern Irish government to hold a summit on the rise in listed building arson attacks, the 2011 fire was just the first of many.

The Herdman brothers founded the mill in 1832 with a mission that diverged radically from the horror stories of slums and poor working conditions in other parts of the UK. The brothers built a school, housing, and churches. It was a non-sectarian village, and it remained that way through the Troubles.

“Herdman’s used to supply all recreational services to the village. Then they closed in 2004, and gradually everything started to slow down”, said one local resident, who asked to remain anonymous.

Despite efforts to keep the mill in local hands and hopes to finish the restoration work Herdmans Limited had started in the early 2000s, the 62-acre site was sold to Irish businessman Karol McElhinney.

He applied to demolish the buildings three times. When those plans fell through, he successfully applied to remove the industrial metal chutes connecting the mill buildings. Local people described lorries loaded with metal leaving the site, estimating the total cost of removed scrap metal to be in the millions.

“He left it just a shell”, the local resident said.

McElhinney then applied to build an anaerobic digester, to turn animal waste into energy, but residents of the local village Sion Mills protested that the project would harm their health and pollute the River Mourne that the mill sits on.

After a months-long planning dispute between residents and McElhinney, the Planning Appeals Commission ruled against constructing the digester.

Nothing was done to secure the site, and waves of vandalism followed, said local residents.

McElhinney declined to comment on Herdman’s Mill and his experience owning the property.

In 2014, McElhinney sold most of the property to a lottery winner, Margaret Loughrey, while retaining the hydro-electric power plant that still generates electricity today.

Those who opposed the anaerobic digester celebrated the change in ownership, but their relief was short-lived. The mill would endure another decade of neglect and five more severe arson attacks.

Loughrey had an ambitious vision for the property – an amusement park with attractions like a bowling alley and go-karting track.

“We knew it was going to be a disaster because the Sion Mills Buildings Preservation Trust couldn’t even restore the site with the top business guys. How was she going to do it? She had no idea”, said Celia Ferguson, founder of The Sion Mills Buildings Preservation Trust and the last living member of the Herdman family.

As obstacles and Loughrey’s money troubles piled up, the buildings were once again vulnerable. In 2018, an arson attack reportedly left the building “smouldering”. Repeated attacks had gutted the buildings’ interiors.

A court order gave the Preservation Trust ownership of part of the complex to combat the property’s deterioration in 2016, but the Trust is still trying to raise enough money for a restoration project.

The listed buildings are “just deteriorating”, Ferguson said. “But we’re told that the structure is still the way it was built. It doesn’t have wooden ceilings. It’s made of brick. So in theory it can be restored again, even if it's deteriorating”.

Herdman’s Mill was sold one last time in 2021 to the fruit juice company Mulrines. The juice factory is housed in new buildings, and they have agreed to let the Trust see its restoration plans through.

Funding for heritage projects is hard to come by and austerity policies have stripped many UK councils of spare funds.

In Northern Ireland, the budget for helping owners of listed buildings has dropped from four or five million to £200,000 since 2015, Graham at Ulster Architectural Heritage, said.

One in five councils in England are at risk of bankruptcy and one in four in Scotland. Heritage conservation is unlikely to be at the top of their priority lists either.

Because of financial constraints, councils across the UK are reluctant to serve enforcement notices on buildings that are falling into disrepair, leaving them at further risk of arson.

Councillor Darren Rodwell, building safety spokesperson for the Local Government Association, warned that a lack of money can prevent councils from buying buildings or forcing absentee owners to carry out work. “The options open to local authorities to bring derelict buildings back into use when an owner is continuing to pay council tax are quite limited”, he said.

Scotland-based conservation architect Pat Lorimer is critical of the enforcement process and the powers available to councils. “It's an unsatisfactory system”.

He said that if owners do not carry out the required work to the building, the councils have to do it themselves with taxpayers’ money and then try to seek compensation. Taking owners to court also costs money.

“There's a soft spot which people take advantage of”, said Lorimer.

The White Hart Lodge in Bristol, England, days after it went up in flames. The former pub had been derelict since 2021. April 2024. Aidan O'Donnell.

Heritage groups say it can be unfair to accuse councils of doing nothing while developers allow a listed building to deteriorate.

Connor McNeil, a Conservation Advisor at the Victorian Society, drew a contrast between the north and south of England.

“Somewhere like Westminster City Council has 17 conservation officers. And you can have a local authority somewhere in the country like Nuneaton, which doesn't even have a conservation officer”.

He said that where councils do not have a conservation officer, groups like the Victorian Society sometimes have to step in.

“We all have about three case workers covering the country”, said McNeil. “It's impossible for us to respond to every application in the level of detail that it needs”.

Sebastian Graham also worries about self-censorship from heritage conservation groups. He said people are sometimes afraid of publishing things that make councils and national governments look bad.

“If you stand out from the rest, you’re not going to get funding. That’s a huge fear”, he explained.

Graham has never had funding taken away for speaking up, but it’s “something that does play in the back of your mind sometimes when you do come and stand out on a particular issue”, he said.

Some of our sources were less sympathetic to councils.

McNeil said some councils disregard their legal obligation to consult national amenity groups on applications to partially or completely demolish listed buildings.

Another issue is oversight when councils decide to sell their buildings to private owners.

In February this year, Stoke-on-Trent City Council announced it was preparing an “ethical framework” that would require it to do background checks on prospective buyers of council buildings and would give it power to have a say over the future of the building.

This comes after Grade II Portland House was turned into a cannabis farm within two years of being sold by the council. Months after the cannabis factory was discovered by police in January 2022, it was hit by a fire.

This scheme will apply to a minority of listed buildings. According to our database, many derelict listed buildings were never owned by councils or had been in private ownership for years before the fires.

Even when councils do take action, there’s no guarantee it will help.

Ayr Station Hotel, a listed 1885 building near the Scottish west coast, was a crumbling but active hotel business in 2010 when it was bought by Malaysian businessman Sunny Ung for £750,000.

In 2013, Ung closed the hotel and around the same time was served a Dangerous Buildings notice by the council. ScotRail reportedly had to attach netting to the building to prevent debris from the hotel falling onto the train station below.

A ten-year battle over the derelict listed building followed, with South Ayrshire Council and rail operators on one side, and the unresponsive Ung on the other.

Little appears to have happened with the building in the first five years after the Dangerous Building notice, and Ung was served another in March 2018.

That summer, an “exclusion zone” was created around the train station because parts of the hotel were crumbling onto the platforms and station.

Later, in 2021, South Ayrshire Council blocked the owner from selling the building to another party. The council had rejected Ung’s offer of financial compensation, as it was reportedly far below the amount spent by the council to manage the building’s deterioration.

2023 proved to be decisive for the old hotel. Early in the year, South Ayrshire Council agreed to spend hundreds of thousands of pounds of taxpayer money to maintain scaffolding on the building. Then in May, the rear of the building was hit by a fire, with two teenage boys arrested and charged with starting it.

September was the most eventful month of all. A report from a structural engineer found that the building was “in much better condition” than initially thought. But the estimated cost of nine million pounds to bring it back into use was millions more than the cost of demolition.

That month, the council committed hundreds of thousands of pounds in additional funds to maintain the building. It was now pursuing Ung in Malaysian courts for over £1.3 million.

On 25 September, Ayr Station Hotel was hit with another suspected arson attack. This fire was much more destructive than the one in May, described by the Daily Record as “devastating” and leaving “the hotel's south wing completely gutted”.

On the same day as the fire, The Herald published an opinion piece which asked “whether the council have properly looked at the alternatives to demolition”.

This sentiment was shared by Esther Clark, a campaigner working to have the building “saved”. She insisted that the council and Network Rail wanted to see the hotel knocked down even before Ung bought the building, as part of plans for a new transport hub.

According to her, they never wanted to see the building restored and intervened to prevent Ung from selling it to someone who would.

Since the fire, several demolitions have taken place, with SAVE Britain’s Heritage repeatedly accusing South Ayrshire Council of conducting excessive demolition and engaging in a culture of secrecy around the justifications.

Last month, South Ayrshire Council announced that the tower and half of the northern section of the building would be demolished due to safety risk from fire damage. SAVE Britain’s Heritage again accused the council of operating an “apparent opaque process" around the demolition.

The council point out that they’re left with little choice once damaged parts of the building become a risk to the public, and that the remaining parts of the hotel will be preserved.

Former Scottish First Minister Humza Yousaf was eager to see “the building demolished” due to the economic damage caused by the ongoing lack of rail services in Ayr.

In the latest twist to the ongoing saga, on 1 May, the demolition of part of Ayr Station Hotel was halted following a legal challenge from owner Sunny Ung.

The building remains Ung’s responsibility, Ben Oakley at SAVE Britain’s heritage said. “It probably wouldn’t have fallen or burned down if it hadn’t been left in that state in the first place by the owner”.

“If you own your land, you are responsible for it. But the way it is right now, you feel like these owners aren’t having to bear any responsibility”, Oakley said.

There is a trend for owners to neglect properties after their development dreams fail to get planning approval or community consent.

Connor McNeil of the Victorian Society is critical of owners who appear uninterested in working within the system. A listed building “does have constraints. We would never pretend that it doesn't. But that's something that has to be worked with, rather than worked against”.

“If you're taking on a building and you want to get a maximum number of flats out of it then you're taking the wrong approach to a listed building”, he said.

Sam Stafford of the Home Builders Federation, which represents private sector homebuilders in England and Wales, acknowledges that some developers might deliberately allow a building to fall into disrepair.

“It's conceivable that somebody would buy a heritage asset, do nothing with it for 20 years, wait for it to fall down and then go to the local authority and say ‘this building is beyond repair, I'm going to knock it down and build something else’”.

Although he pointed out that home builders are not able to sit on land in the same way as developers.

The Victorian Society accuses the company Barry Howard Homes of this very approach. This company bought Overstone Hall in the Northamptonshire countryside in 2015 – the same year the large listed house made the Victorian Society's list of the 10 most endangered Victorian and Edwardian buildings. It had already been severely damaged in a 2001 fire.

In April 2017, local residents formed the group Overstone RUINED, to oppose plans from Barry Howard Homes to build 200 homes on and around the site. The following year, the company submitted the plans, which included restoration of the listed building for use as flats.

Barry Howard Homes was eventually given permission to restore the building but not to convert it into accommodation or for 52 homes to be built around it. Despite Barry Howard himself saying he had “no problem with the decision”, no restoration was forthcoming.

Two years later, in 2022, the owner applied for permission to demolish the building. The application stated that Overstone Hall is “at the end of the road” and that “the Applicant has taken all reasonable action to arrest the decline of the remaining parts of the Hall”. As evidence it cited the “installation of a tarpaulin”, which had “subsequently deteriorated by the effect of the wind”.

Four months later in March 2023, Overstone Hall experienced a “huge blaze”, with a spokesperson from Northamptonshire Fire and Rescue Service describing “signs of forced entry”.

One local resident told us she saw smoke from a nearby field. “I was like, ‘Oh my goodness me, it’s on fire again’”.

Alex Howes, of Northampton Civic Society, says people in the area have “conspiracy theories” about the fire. The local resident we spoke to said the same. But Howes believes it was a simpler case of negligence.

“Whether it's true or not almost doesn't matter. I think it's the fact that it's a combination of negligence, but also the fact that a lot of these developers and the council are just not open about the building”.

He believes the company had only minimal security in place and ultimately failed to make the site safe.

In May 2023, the Victorian Society – consulted by West Northamptonshire Council’s planning department on the 2022 demolition application – wrote a vigorous rejection of Barry Howard Homes’s proposal to demolish the building. The owner’s justification for demolition, according to the Victorian Society, was “primarily based on the maximum profit the owners would like to make from the site and not on securing the future of this neglected heritage asset”.

We contacted Barry Howard for an interview in February but never heard back. According to an administrator at his office, Howard has refused to speak with other journalists on similar topics.

In June 2023, the BBC reported that over 600 objections to the building’s demolition had been lodged. Historic England were reported to be urging West Northamptonshire Council to commission a feasibility study on how it could be preserved.

As of 9 May 2024, the 2022 application to demolish the building had not been decided on by the council, despite a target deadline of 30 April. Discussions between the council and the owner about the future of the building continue.

Howes was very critical of Barry Howard Homes, but also of the council. “I think generally there's just no confidence in the council's ability to enforce planning permission, or the fact that they really care about the local environment”.

Sam Stafford at the Home Builders Federation agreed. “Let's call those kind of people the poachers”, he said. “What you're then looking for is for the local authority and heritage England and the custodians to be smarter than the poachers”.

“But I guess what you wonder is, Historic England and local authorities, do they have the resources to be able to monitor and police?”, he said.

Stafford and other development experts we spoke to stressed that the sector is opportunistic and profit-driven. And right now, the housing economy doesn’t encourage conservation.

In 2012, the first Cameron government removed VAT-exemptions for listed buildings, undermining the financial incentives for developers to protect them. Any alterations to listed buildings now come with 20% VAT. New build projects are VAT-free.

So, if a listed building could be demolished or allowed to deteriorate to the point of collapse, owners would no longer need to pay VAT and they’d have a cleared site to build on.

Tom Whitfield of the Georgian Group said his team is available to help developers find a middle ground that balances profitable use and heritage conservation.

“There are private developers who are very receptive to that and who do reach out to us at an early stage in developing the project”.

“Then again, there are applicants who will be quite intransigent and unwilling to engage with us at any point in the process”.

We asked multiple people involved in conservation whether heritage bodies can sometimes be too tough on developers who try to bring buildings back into use.

“Sometimes we do take a strong position on certain elements”, said Whitfield. But he insists that part of the Georgian Group’s function is to assist developers.

“Conservation doesn't mean keeping something unchanged. We recognise that we do need to be flexible”.

Available land is another constraint. Developers we spoke to explained that very little land is coming to the market for people to build on, especially in built-up areas. So listed buildings can remain attractive, despite the associated costs.

The former nightclub in Newport, Wales – fire-gutted but still listed – is going to be turned into 37 social housing apartments by public housing developer Linc Cymru.

The waiting list for social housing in Newport has over 9,000 people, and this building has stood empty and deteriorating for more than a decade.

When land becomes available, especially in city centres where demand is soaring, developers like Linc Cymru feel pressure to buy it up, said Chris Cater, the project manager for the site.

“Nobody wants to see homelessness, nobody wants to see people sofa surfing, so we’ve got to deliver the social housing”, Cater said.

On the day we interviewed Cater and his colleague Shelly Leonard, someone had set up a tent behind the burned-out club building. “That’s the irony of today”, said Leonard, Linc Cymru’s social value officer. “That picture speaks a thousand words”.

After six years of construction, the church next door that also burned down has been restored. According to Cleverly, the project cost seven million pounds, paid for by insurance and grants.

“We would've never been able to raise that on our own”, he said. When the church wanted to do some interior restoration work in 2018, they only managed to raise £25,000 of their £300,000 goal.

The church’s listed exterior has been restored to its original state. On the inside, glass staircases and white walls contrast with old bricks, stones, and stained glass.

The club has remained gutted, but Linc Cymru will start construction on its housing project this year. Though only the club’s facade will be saved, Linc Cymru’s project is even more expensive.

It is expected to cost about eight million pounds, Cater said.

He thinks that preserving the facade alone will cost £400,000. Retaining it has added hundreds of thousands of pounds and delayed the project by two years, he said.

“We've had to use a steel frame on this because it's got to hold the weight of the facade and keep it from falling over when the rest of the building is demolished”, he said.

Most people we spoke to agree that the listed building system is fit for purpose – it just lacks the resources it needs.

“It's almost as if it's ‘job’s done’ at listing”, said Sam Stafford at the Home Builders Federation.

“You really want the local authority or Historic England to be a bit more proactive in working with those new developers to find viable uses for these buildings because they can't be museum pieces”, he said.

Stafford said he’s a “pragmatist”. He understands the pressures for both developers and conservation groups and believes the planning system should mediate between the two.

The UK has a discretionary planning system, he said. Council planning committees, and even higher levels of government, decide the fate of properties on a case by case basis.

There are pros and cons to a discretionary system, “but the health and vibrancy of the planning system at present is not in a happy place. Good things happen, but more often than not, they happen despite the planning system rather than because of it”, he said.

The planning system is often criticised for being too slow. Connor McNeil at the Victorian Society said, “the only way you’re going to make it faster is you employ more people to do the work”.

Pat Lorimer believes policies need to change, too.

He says the government should empower local authorities with harsher punishments for developers who do not comply with enforcement notices.

He also thinks making the cost of restoring listed buildings VAT-free again would help.

“I don't think the financial implications from a government's tax rating point of view would be that great”.

While it was a limited supply of land that led Linc Cymru to buy the former music venue in Newport, they now see its listed status as an advantage. The social housing developer has a new brand, “What Once Stood”, that they hope will bring in additional funding, but which will also highlight the history of the buildings.

Thank you to the local media outlets and Local Democracy Reporting Service whose reporting underpins our database and article.